- Home

- Laurence Miall

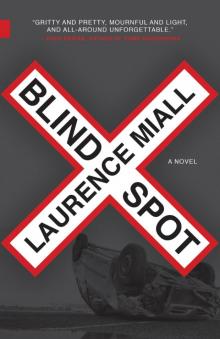

Blind Spot Page 7

Blind Spot Read online

Page 7

We turned onto the last stage of the journey in the darkness of the quiet road where we lived.

“You seem very contemplative,” she said.

“You seem that way yourself.”

“I’m tired. What about you?”

“I was thinking about how I don’t want to go back to Vancouver.”

“No one can make you.”

We stopped at the pathway to my house.

“Do you want to come in?” I said.

“Luke… What are you saying?”

“For a final drink,” I said. “For a drink between friends. That’s what I mean.”

“That’s really what you mean?”

She fixed me with an intent look, and her lips creased upwards. She didn’t believe me.

“We’re friends now. I’ve told you things I’ve never told anyone,” I said.

“I’m honoured. But I can’t come inside. Anyway, we finished all the wine, remember?”

“There’s still some scotch and I think some cognac that my parents stashed away.”

“No, Luke.” Julianne embraced me. “I’ll see you soon,” she said.

14

There must have been far more liquor consumed that night than I had realized, because the next day I woke up in the grip of a vicious hangover. To make it worse, my sister was standing over me, kicking my feet.

“Wake up, Luke. It’s already twelve. Wake up.”

The light was streaming in through the window, burning my eyes. After acknowledging her, I forced my head around to see what kind of chaos my evening with Julianne had left behind. Sure enough, despite my previous cleaning efforts, the place had now returned to its usual disorder. Our dishes were still strewn on the table, there were some old photo albums lying on the floor that I’d been showing her, and my clothes were scattered about from my late-night return home. And even I could tell that I smelled like a wino.

“Late night?” she said.

“Yes.”

“Being in the old house brings back the old Luke, eh?”

It appeared to amuse her.

After my usual coffee and cigarette, during which time she busied herself with sorting through more junk, I was in a fit state to sit down and talk to her.

“The paint job is looking good,” Laura said. “It looks like you only have a few more days of work left.”

“Weather permitting,” I said.

“Are you able to stay a few more days?”

“Able? Able how?”

“To take time off from work, I mean.”

“No problem. I’ll just call them. It doesn’t matter.”

“Is everything all right, Luke? You don’t seem very keen on going back.”

I could have bluffed my way through this and reassured her that everything was perfectly fine, but I suddenly felt incredibly weary of acting.

“No, I’m not very keen on going back.”

I proceeded to tell her how Vancouver had completely lost its luster. I wasn’t going anywhere; I’d gotten stuck in a rut. And my relationship was in a rut. Everything had become a compromise. Stephie said we needed a new bed, so I went and forked out a grand for a new bed. Stephie insisted on seeing her parents every month, so we found ourselves on the ferry every month so we could go exchange banalities with her parents. Stephie said we should move to Kitsilano, so we had moved to Kitsilano. Stephie said we should get pregnant in about two years, so we were planning on getting pregnant in two years. I had never imagined, in all my childhood, in all my adolescence, and in all the struggles of my twenties, that I would become so ordinary.

I was angry about it — and maybe came off sounding even angrier — because the hangover’s miserable and slow march through my body was causing me immense irritation.

“I didn’t realize you were this unhappy.”

“Not unhappy,” I said. “I don’t want to come off sounding depressed, or self-pitying. I’m just frustrated, and bored maybe, too. Nothing is terribly wrong, but nothing is right either. It’s just this dissatisfying in-between. Some days I wish something truly bad would happen so that I would have something genuine to worry about.”

Laura looked at me curiously.

“Something terrible has happened,” she said. “Haven’t you noticed?”

I held her gaze for several seconds or more before I got it. And by then, it was too late. She was crying.

“Laura, I’m sorry. Jesus, that was an incredibly stupid thing to say.”

“You’re a selfish prick, Luke,” she sobbed. “I just can’t believe you. I didn’t ever think you much cared about Mom and Dad, but now I know for sure you didn’t.”

“That’s not true.”

“I never understood what you had against them. And why, after all those years, you didn’t just get over it.”

“I loved them like you did, Laura.”

“No you didn’t.” She looked up and the tears were already drying as her eyes became more resolute. “You don’t have to go on pretending to me.”

“My relationship with them was… was complicated.”

“Whatever it was, you’re living in this house like a teenager, and I don’t know why you want to stay. We’re selling this house, Luke.

It’s not yours. You can’t treat it like your personal dive. You’ve been smoking in here, too. You know they would never have allowed that.”

“I just had a couple last night. I had company over.”

“Who?”

“A neighbour from a few doors down.”

“A girl?”

“Does it matter?”

“I’m assuming it was a girl.”

“Nothing’s going on.”

“It’s not my business, Luke. I just don’t understand what you’re doing here. You’ve never wanted to spend any time here before. What are you doing here? Running away from something?”

“I’m helping out.”

“I just don’t understand why you’ve chosen now to help out. Howard and I could take care of everything.”

“Why don’t you just accept my help, Laura? Stop trying to understand it and just let me do it.”

There was an edge to my voice. She had started to anger me. She was acting as if she were the sole custodian of our parents’ memory. I was the errant son and she was the responsible and loving daughter.

She sighed.

“Can you at least take better care of this place?”

Later, while I was helping her haul a load of junk to the shed for later removal to the dump, she asked me about my strange living arrangement. It puzzled her why I didn’t sleep in one of the upstairs bedrooms.

I replied honestly.

“I don’t feel comfortable up there,” I said. “I don’t feel like I belong.”

She fumbled with the lock of the shed, finally springing it open, and we dragged our heavy garbage bags inside.

“You don’t feel like you belong,” she echoed.

“No.”

“You could sleep in my old room.”

“I know. I just feel weird. I can’t explain it. The upstairs feels private to me, and I don’t belong there.”

“You used to stay there when you visited.”

“I know. It felt weird then, too. When Stephie and I were here, I felt like I was intruding on Mom and Dad. Stephie and I were whispering all night like little kids on a slumber party. I kept feeling like I was going to get told off.”

“Well, they certainly would have told you off for smoking in the house like you did last night.”

I laughed.

“I bet they would.”

“You would’ve had it coming.”

She locked the shed and we returned to the patio. It was three o’clock, and the sun had already achieved the full extent of its day’s ambitions. I lit a cigarette and sat down on one of the lawn chairs. Laura hovered for a second, as if unsure whether to join me or keep working. Then she pulled up a chair beside me.

For several minutes, neither of us

spoke. My cigarette burned down to the end, I stubbed it out on the sole of my shoe, and then lit another one.

“Laura, I know you think I’m a selfish prick, but don’t think that Mom and Dad leaving us means nothing to me. It has turned my world on its head. I can’t explain it very well, but it has. I feel robbed. You knew them, but I didn’t know them, and I’ve been robbed of the opportunity to get to know them.”

I had the impression that I was making her uncomfortable. She reached down and untied the laces of her sneakers, then tied them up again more tightly.

“Do you understand?” I said.

“Sure, Luke. I just never know how genuine you’re being. I remember how many times you lied to Mom and Dad when we were growing up. How deceitful you were. I learned not to trust you. I remember when I first caught you in a lie. You asked to buy some fancy scientific calculator for school, and then you used the money to buy a carton of cigarettes. You didn’t realize it, but I saw you. I saw you take the money and simply go right across the road to the IGA and come out with the carton under your arm. Then you jumped back on your bike and disappeared, probably to go see your friend Joel or someone. I remember wondering how you planned to get away with it. When you came back that night, Mom and Dad asked to see the calculator. You said the store had sold out. It would be coming in next week. I watched your face as you lied. You were completely calm. You shocked me. And you disgusted me. But I didn’t say anything. By the time next week came around, Mom and Dad were so busy, as they always were, that they’d totally forgotten about the calculator.”

I smiled. I could remember buying that carton of cigarettes. Joel had been especially impressed. I had told him I’d stolen them out of the back of a delivery truck.

“I know I was a lying little shit,” I said to Laura. “But that was a long time ago.”

“I understand that, Luke. I know you’ve changed. That’s why I’m nice to you. Do you see that? I’m actually nice to you now. Back when we were kids, I simply ignored you, and I didn’t want anything to do with you. To my friends I said, ‘My brother is a little punk.’ I’m not like that anymore. Still, I’m aware there are always two sides to you. There’s what you choose to tell people, and there’s what you choose not to tell people. And they could be completely different. Take this girl who was round last night, for example. I know better than to ask you what is happening. I don’t want to know. I like Stephie. She’s a sweet girl. And if you’re doing anything to hurt her, I’m going to be angry with you.”

Silence prevailed, but this time, it was an uneasy silence. At last, we simply got back to work.

15

I went to call on Julianne several times that weekend, but she wasn’t home. Nobody was home. She had mentioned living with several roommates, so I found this very strange. I circled the house from front to back, trying to find a sign of her. Giving onto the alleyway was a garage. The door was open, but the garage was empty. There had been a car there recently — you could see some fresh drops of oil on a flattened cardboard box on the floor. In the back garden, there was a child’s tricycle lying on its side. When I discovered that, I thought I’d come to the wrong house entirely. I returned to the street and surveyed the neighbouring houses. But she couldn’t possibly live in either of the neighbouring houses. Through the window of one of them, I saw a family sitting down to dinner. In the other, there was a middle-aged man sitting in the half-light watching TV. I had seen him pull up in his car several hours earlier. He couldn’t be one of Julianne’s roommates. He was simply too old. Besides, she had mentioned living three houses from mine. This house was only two doors down.

I looked at what I believed to be Julianne’s house again. Flanking the sidewalk was a row of six lanterns on iron poles buried in the grass. The lanterns were about four feet high. A faint glow emanated from each one. This also struck me as odd. The house was blacker than night, but somebody had turned on these lanterns? But maybe the lanterns were on some kind of a timer switch.

I was becoming edgy. Julianne had entered my life one moment and seemingly abandoned it the next.

There was a phone call from Stephie early in the morning. We had not talked in three days. I got this vague sense that she was trying to catch me doing something I shouldn’t. It was seven o’clock, for fuck’s sake. The conversation swerved quickly and violently into an argument. I hadn’t yet purchased a return ticket, and she was incensed about it. She said that it was clear I had no intention of ever coming home. Her parents were asking after me, and it was humiliating to not know how to answer them. I said she was being selfish. My family had to come first right now. I tried to reassure her that she was important to me, as she always had been. She replied, if she was so important to me, how come I hadn’t told her that I’d moved into my parents’ house? Why hadn’t I given her my new number? Why had she been forced to track me down through my sister?

I said I’d be coming home next week and to stop worrying about it.

On Monday, I was up on the ladder at ten o’clock, expecting to see Julianne, but I waited all morning in vain. I eventually climbed down from the ladder and called on her at home. Still nobody was there. The situation was starting to make me a little crazy. I had slept poorly and my nerves were frayed. When I climbed up the ladder again, I was distinctly afraid of the height. I thought, If I fall and die, I will have accomplished nothing. My life will be in limbo, and everyone close to me will simply remember the last argument they had with me. It will be a sorry end to my life.

I got down from the ladder. I went into the house, not really sure what I intended to do. I remember standing at the bottom of the stairs, looking up. I was convincing myself that it would be a good idea, and helpful of me, to go up there and continue the work of sorting out my parents’ belongings. Suddenly, the phone rang. I jumped. I ran to answer it. Laura was talking hurriedly at me. She was on her cell phone downtown. I could hear the traffic in the background. It turned out that there was an appointment for both of us to see the lawyer in two hours’ time. We were supposed to finalize the details of the will. She had totally forgotten about it until a reminder call five minutes ago. She was stressed out, and “losing my mind a bit,” she said. Work was crazy and she’d just had a big argument with her son Tom about a violent pornography site she’d found him looking at on the computer. What’s more, in the middle of the night, somebody had stolen the barbecue from her backyard. I tried to reassure her that everything would be all right. It was hard to prioritize all these conflicting worries. Was Tom’s Internet use or the theft the biggest worry? Or work, or the will? She was lumping everything together, saying everything was going wrong, everything.

“Let’s meet in an hour,” I said. “Where’s the lawyer’s office?”

“On Whyte,” she said. “It’s Mom and Dad’s lawyer.”

“All right. Let’s meet at the Black Dog in one hour, you can calm your nerves, then we’ll go deal with the will.”

“The Black Dog is a bar, Luke.”

“Well, suggest something else. I don’t know anywhere else. I haven’t lived here in ten years, remember.”

I was briefly annoyed by her puritanical attitude.

“Okay, we’ll meet at the Black Dog.”

It was a good choice, because after I’d persuaded her to have a pint, she relaxed and could see that her problems weren’t so overwhelming. The theft of the barbecue was probably the work of amateurs. Professional thieves could have broken into the house itself and made off with a lot more. Work was crazy, but it became clear that she was the most experienced graphic designer in the department. Her boss had told her that she was irreplaceable. They weren’t going to suddenly end her contract because she had to take a little time off to deal with her parents’ death.

“Do you think they’re heartless bastards?” I asked her.

She smiled.

“No, they’re not heartless bastards.”

“Okay, then. That leaves Tom’s Internet interests.”

“That was horrible. I knocked on his door to say I was coming in and he didn’t answer and I just came in. He was looking at the most graphic video I’ve ever seen. We were both so embarrassed. Thank God he wasn’t actually…”

“Jerking off?”

“Thanks for the directness, Luke.”

“So, what was he looking at?”

“You know…”

“No, I don’t know. You said violent pornography on the phone.”

“Well, it looked violent to me. It was a girl and three guys. I’m standing there looking at my son and the dirty movie is playing in the background.”

“They were just having sex with her?”

“Well, yeah. Having sex, I guess. It just shocks you, seeing it. And Tom’s only thirteen.”

“If we’d had the Internet when I was thirteen, I probably would’ve been looking at that.”

“It can’t be healthy.”

“Well, I don’t know.”

“When I talked about it to Howard, we agreed to take the computer out of Tom’s room and put it in the basement where everyone can use it.”

“Problem solved, then.”

She smiled at long last.

“You’ll understand how shocking this kind of thing can be once you have kids.”

“But it wasn’t anything illegal he was looking at.”

“Uh, no. I guess not. But it’s nothing a thirteen-year-old should see.”

Blind Spot

Blind Spot