- Home

- Laurence Miall

Blind Spot Page 2

Blind Spot Read online

Page 2

Once we were out on the front steps, Joel turned to pull shut the front door. I heard the click of the latch falling into place, and I wanted to start running. But he had frozen there. He was staring at the door.

There was a sort of wreath hanging there, and etched on the wood in cheery yellow letters it said, “Welcome to the Violets’ residence.”

“Violet,” he said. “That’s your name.”

My first instinct was denial.

“What are you talking about?”

He was shaking his head.

“How many Violets are there? This is your neighbourhood. I know it is. How many Violets could there be living around here?”

“I don’t know.”

“That’s why you were acting so weird.”

“I wasn’t acting weird.”

“You were.”

I had to confess it. Yes, it was my house.

“You’re robbing your own house?” he said, incredulously.

I retorted accusatively, “You steal money and smokes from your mom all the time.”

“That’s not like this.” All of a sudden, he had become very moral. “You’re breaking into your own parents’ house. Fucking unbelievable.”

For a moment, I could not speak.

“What are we going to do?” he asked.

“I don’t care,” I said, feigning bravado. “Let’s sell it. Let’s go to the pawnshop. My parents are saps.”

“Sap” was one of the many words I’d stolen from him. I was trembling. He looked at me witheringly and brushed past me on the front steps. We beat a hasty retreat. We were supposed to take the bus together from Whyte Avenue, but I lost my nerve. I didn’t want to sell the stuff. I asked him if we could store it at his place.

“And what if my mom finds this stuff?” he asked. “She’s gonna wonder where I got it.”

“We’ll get rid of it real quick.”

“If you’re not coming with me, that’s your problem. I’m going right now. I’m going to sell this shit. You don’t want to hold onto hot goods. The pigs can smell it.”

We parted ways on Whyte Avenue. We agreed to split the profits fifty-fifty. On my own again, I wondered if I should go home. Maybe I should run away. There was going to be hell to pay once my parents discovered they’d been robbed. How had I ever thought I would be able to conceal this from them? I knew that when I walked in the door, my crime would be emblazoned on my face.

I could not go home. I had never wanted parents anyway. I started walking eastwards, got to 99th Street, then 91st Street, and finally I descended into the Mill Creek Ravine, usually the outer limit of my existence. I had played here many days of the summer. The ravine joined up with the river valley. If I followed the river valley, I would get somewhere. I would escape the scene of my downfall. It would be the start of a new life.

2

After dark, I returned home. I couldn’t live in the river valley on my own, a boy of eleven. My parents had long ago found the window gaping open. They knew of every single missing possession. There was relief that I wasn’t there when the break in happened. I said that I had gone out to buy cough syrup. It was a pathetic excuse. They asked me, where was I hiding this cough syrup? They were already suspicious. I said that it was right here in my pocket.

Show us, they said.

No cough syrup. The story quickly unraveled.

Then the most important thing was protecting my reputation. I could cope with my parents thinking less of me, but losing face to Joel would be to lose everything. I did not mention his involvement in the crime. I said I’d taken everything to the pawnshop and sold it. Where is this pawnshop of which you speak, Luke? I dodged the question. We don’t have to go to the pawnshop, I said. It’s my fault. I’ll go get the stolen goods tomorrow. But where is the money they gave you for our belongings, Luke? I don’t have it, I was forced to admit.

Why not?

Another story unraveled just as quickly as the first.

This was where I was undone. It was not the break in on my own home that really killed them. It was that I lied about it not once, but twice, before the truth came out.

I was lost. I burst into tears, knowing with certainty that the life I had known was over. I confessed everything. I confessed that as we spoke, Joel was probably coming home from the pawnshop with the money in his hand from the sale.

Things were suddenly moving very quickly. My dad was already getting his coat on.

“What’s Joel’s address?”

I told him.

“I’ll go straighten this out.”

He returned home an hour later. He had the hockey bag. Joel couldn’t sell a thing. The pawnshop owner wouldn’t take such valuable things from a child. Apparently, Joel’s mother had slapped her son across the ear right in front of my father.

“I don’t ever want to have to do something like this again,” my father said to me.

My mother asked me, “Why did you do it?” She had already asked this a dozen times, but only recently had my grief subsided enough that she might expect a response.

“I don’t know.”

“Why? Don’t we give you a good enough allowance?”

I could not look at them. I stared hopelessly at my two feet that dangled seemingly ten metres away at the end of my legs. I was suddenly exhausted. It was past ten o’clock.

“Were you trying to impress your friend?”

This was exactly the truth, but I would not confess it. And what was more, I hated my mother for saying it, and I hated my father for agreeing. “That must be it,” he said. “It was to impress the older kid.” I hated them for voicing what my intentions were. I didn’t want them to understand me. I wanted to be beyond their understanding for the rest of my days.

Two months passed, and I was out buying some cigarettes from a store on 99th Street. I spotted Joel in the parking lot with a friend that I’d never seen before, riding a beaten-up bike. I watched the two of them from behind the grimy store window. Joel was talking casually while nonchalantly trying to keep his balance on his immobile bike. Every couple of seconds, he had to put a foot to the ground to stop himself from falling over. His friend, meanwhile, was picking stuff out of his ear and examining his fingertip.

Sooner or later, I would have to exit the store, but I didn’t like my chances if I exited right away. I’d had zero news of Joel; my parents had withdrawn me from judo, and that removed all chance of contact with the kid. But I had to assume that he didn’t think kindly of me.

For a moment, I thought maybe I would get out without incident. Joel manoeuvred his wheel around and seemed to be heading away. But he merely did a circle around his friend, and then pedaled right towards me. In a heartbeat, he came to a skidding halt. He jumped off, swung open the door violently, and there I was, right in front of him.

“Joel,” I said, wanting to greet him without hesitation. He was now blocking the exit. The door chime was ringing out.

“Long time no see,” he said, staring at me, an inscrutable smile spreading across his face.

“Too long,” I said.

“Sure,” he said. “Too long for you, maybe. For me, it would’ve been nice to see you, let’s see, maybe two months ago, when my mom was fuckin’ threatening to kick me out. I took the whole fuckin’ rap for that heist, you squealer.”

My left leg was going to betray me; all my nervous energy was leaking out in that one place. Even though he scared the shit out of me, I still had more respect for him than ever. Especially since, in only two months, he’d added even more words to the lexicon: heist and squealer.

The door chime was still ringing out incessantly. The shopkeeper couldn’t take it anymore.

“Get the hell out the door,” he yelled at us both.

“You’re lucky I didn’t kick your ass,” said Joel, bringing his face close enough to mine that I could smell stale cigarette smoke.

He stepped aside to let me go by. As I moved, he made a pretend jab at my stomach, but his f

ist stopped a couple of inches from doing harm. I recoiled, and he laughed.

A million times you could’ve told me why Joel was an awful role model, but it wouldn’t have changed a thing. I was at exactly the age when the more despicable my parents found someone, the more likely I was to respect him. And removing Joel from my life didn’t help their cause one bit. I still longed to have his unflinching confidence. No one had ever raised him; no one looked out for him. Joel looked out for himself.

I wanted that self-reliance.

Now, so many years later, I’ve arrived.

3

At six in the morning, I received a phone call that woke me from a night of uneasy dreams. I was in Vancouver, and the phone said it was someone from Edmonton. I answered; it was my sister Laura. She described something that was like a scene from a movie. She’d already had several hours to absorb the news. Even so, the telling of it fragmented her speech with sudden squalls and gusts of grief.

Forty-five minutes out of Edmonton, in a hamlet called New Sarepta, lived my parents’ oldest and closest friends, Jacob and Stella Brookfield. Jacob Brookfield was my father’s colleague in the geology department at the university; Stella was his wife and a former classmate of my mother’s. My parents had visited them for dinner and stayed into the small hours of the morning. They had been driving back to Edmonton at two in the morning when their car hit a freight train at an uncontrolled crossing. There were suspicions that alcohol may have been a factor. The police said an autopsy would tell for sure.

And that was as much as Laura could manage. She had to hand over the phone to Howard, her husband. He struggled to find consoling words for me. I felt guilty that he had to go to such an effort.

“Such a… such a terrible, senseless thing,” he said.

He could find the words for any occasion, but not for this. I thought, this is what it must feel like to get stabbed in the gut. There must be at least one second of incredulity. How can this have happened? Then you look down and see that the knife really is lodged in your flesh.

I lay there and stared out of the window at the building on the other side of the street. I imagined distorted faces in the stucco. I waited for something to happen to me. I waited to feel those sounds rise up as they had from my sister: those genuine, undisciplined sounds that sounded like bad weather — the splashes of tears and the bursts of breath — sounds of the animal in the human. But nothing raw or real was in me.

My girlfriend was journeying back from her parents’ home in Victoria, and when she arrived, I would have to tell her. I dreaded this. She considered me emotionally stunted because I was so distant from my family. And she was right.

Stephie had only met my parents once. We visited them during a blazing hot week in the first year of our relationship. Everyone had been oppressed by the weight of the weather. We had limped around Edmonton’s main drag, Whyte Avenue, trying to be enthusiastic about the big summer festival — the Fringe — and trying to say something witty about the clowns and jugglers and escape artists performing in the streets — but every moment, the pervading sense was, let’s get this ordeal over with. And at dinners and lunches, the scrapes of knives and forks were like thunderclaps.

At night, Stephie and I would talk instead of making love, because we didn’t want my parents to hear us (they were right next door), and she would marvel that my parents and I had interacted in this studied, formal, inoffensive manner for my entire adult life.

“It’s like you don’t even like them,” she said.

“I don’t like them.”

She was just about to say something.

“But I love them,” I added.

She was only twenty-one during that first and only visit. She thought that people were closer to their parents than anyone else in the world. After all, they created you, didn’t they? And if you actually loved them, as I claimed to, why was everything so strained and artificial?

I remember the parting at the airport. My father stiffly hugged Stephie. For me, he had a handshake.

I had to get out of the apartment. I wandered all the way down to Jericho Beach. The beaches are always best once the weather turns colder and the volleyball players are gone, and there are no more shirtless men preening themselves like peacocks. You can find a place on the sand to call your own. I stayed there looking at the sea and the mountains. One solitary kayak bobbed in the water. A few passersby disturbed the tranquility, walking their dogs, but little else intruded on my reflection.

Eventually, I picked myself off the sand, feeling the coldness and the rust that had settled into my limbs.

It was in a dreamlike state that I returned home to meet Stephie. She smelled good. She was fresh from the ferry. When I embraced her, the dampness of her hair was soft against my cheek.

“I’m starving,” she said. “I guess you’ve already eaten.”

“No, I haven’t,” I said.

We didn’t kiss. She started looking around for food. I sat down at the kitchen table and watched her going about her business. She was chopping vegetables. She was going to make a stir-fry.

“You’re not going to help me?” she said, eventually.

“My parents are dead,” I replied.

She dropped the knife. She turned and fixed me a frown.

“What?”

“I got a call yesterday from Laura. Mom and Dad are dead. They were killed in a car crash. I’m going home tomorrow.”

She pushed my face into her thick sweater and held me there. It was as if she were my mother.

She asked me how it had happened. I told her the story that Laura and Harold had told me. She was on the verge of tears, but I had not cried. There was something wrong with me. I felt as if I was moving through a fog, my senses muffled and my movements stifled.

“What can I do?” she said.

I shook my head. I didn’t know. What could she do?

“I’m going away tomorrow,” I replied.

“You’re going alone…”

“Yes.”

We ate lunch in silence. Stephie looked at me when we were finished, as if expecting me to do something, but I was just fiddling with my fingernails. There was some sand to scrape out. I wasn’t thinking about my parents. I was thinking about the predicament I was in, having failed to think of bringing her home to Edmonton with me.

Eventually I said, “I want to lie down. Lie down with me.”

We went and lay down on the bed. She curled up, small, into my arms. She was merely a girl. What could she do for me? Nothing. Absolutely nothing. My parents were dead, but I was more worried about her. We’d not spent more than two days apart.

We fell asleep. When we woke up, it was already dark and the apartment was cold. I had left a window open. I went to close it, shivered, and returned. I kissed her. This was our first kiss since she had arrived.

“How long were we sleeping?”

I looked at the clock.

“Four hours or something.”

“It must be dinner time.”

“Yeah.”

“I’m not hungry.”

I replied, “Nor am I.”

There was a stale taste in my mouth and rustiness to my movements. No matter what position I adopted, I felt uncomfortable and awkward.

She sighed heavily, and a little tremor passed through her body.

“Luke, I wish you could take me.”

“I know.”

I sighed too, as if I was just as unhappy as she was.

“Why can’t you take me?”

“It wasn’t me that booked the ticket. Howard booked it.”

“He didn’t think of me? You didn’t mention me?”

I said nothing.

She started to sob. “I’m sorry. I’m just hurt. I’m sorry.”

“I won’t be gone for long,” I whispered, kissing her again.

She closed her eyes, like a child wanting the unpleasantness to go away.

4

Stephie and I shared an apartmen

t in Kitsilano, an upscale neighbourhood in West Vancouver, a place where you do not live, but rather, have a lifestyle. I never wanted to live there. It was Stephie’s choice. She wanted to be close to the university. It made sense. She was a practical girl. You could jump on the number eleven and arrive on campus in ten minutes. And I wasn’t so far from Granville Island, where I worked. In good traffic, I could drive there in half an hour.

I hadn’t come to Vancouver for this. I’d arrived over a decade earlier with the hope of becoming an actor. It was romantic at first, struggling, and making friends with others who were struggling. I rented a tiny studio apartment near Main Street. I had only a camp stove to cook with and a sleeping bag to sleep in, and I walked almost everywhere to save myself bus fare. It kept me in shape.

Keeping in shape — how important that became. I’d wanted to do serious acting, to be in the movies. For a couple of years, I got only bit parts, until my major claim to fame came along. I was cast as the Manspray guy. In my first commercial, I was preening in front of the mirror, spraying deodorant on my armpits and then down to my crotch. There was a little dog — a Jack Russell — jumping up and down beside me, trying to catch a glimpse of me in that great big mirror. I was shirtless, you see. The commercial ran for eighteen months. People loved it. Manspray followed it up with one where I was on a merry-go-round in a playground, all alone and despondent, then I whipped out the deodorant and sprayed myself, and a flock of beautiful young women joined me on the merry-go-round, and we were whizzing around and around together, and a shimmering blue streak emanated from me — it was my Manspray aura — and people loved that commercial too. There were another five Manspray commercials, each a little more derivative than the last, and then the campaign was abandoned entirely. Meanwhile, I had become unemployable outside of television advertising, it seemed. I tried and tried again, and then I simply gave up.

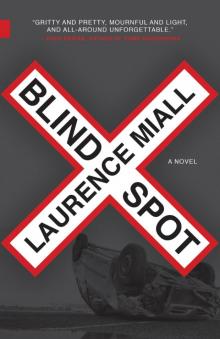

Blind Spot

Blind Spot